Creating brave spaces

An interview with staff from the Office of Equity and Inclusion for Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools

An interview with staff from the Office of Equity and Inclusion for Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools

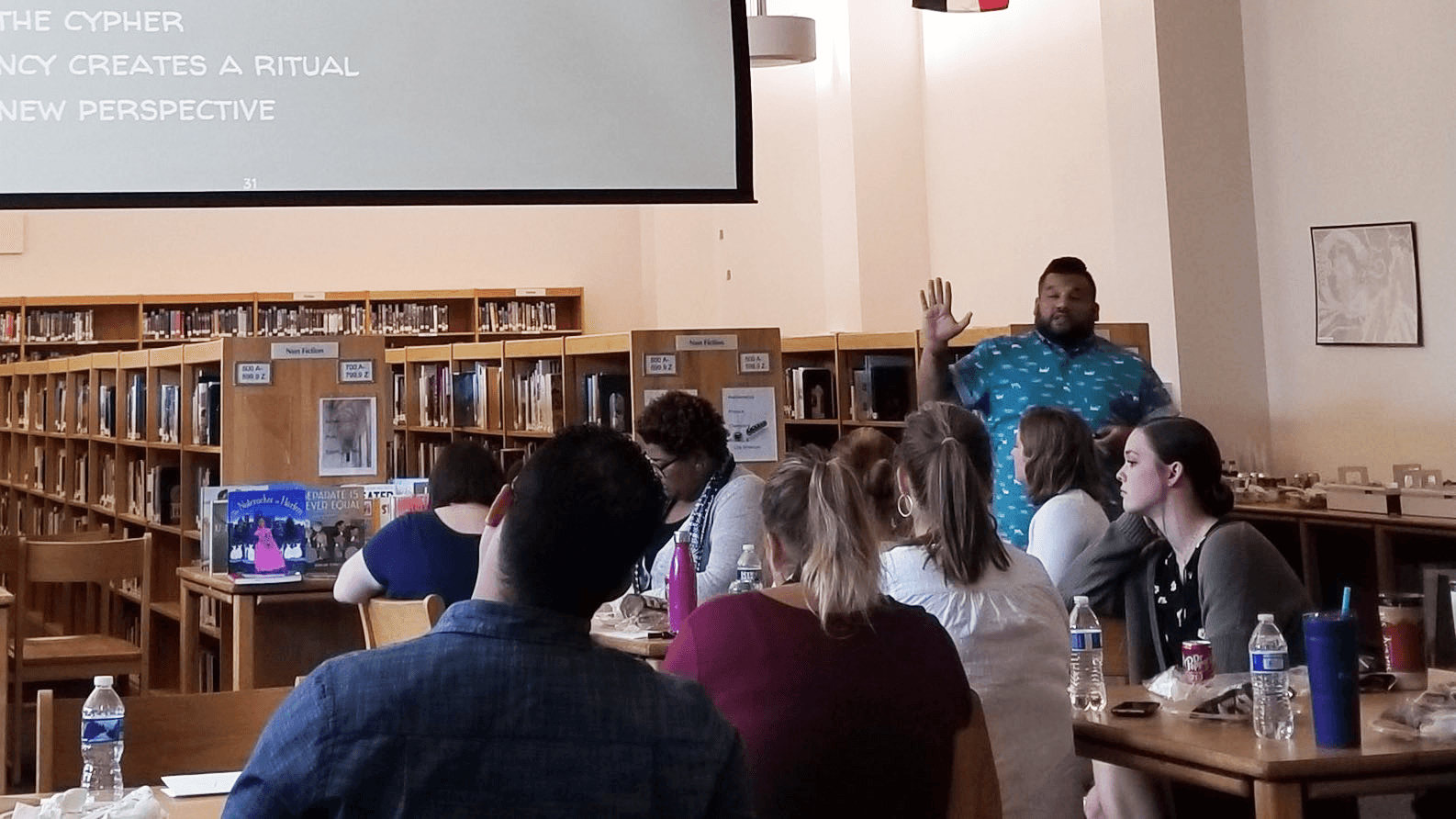

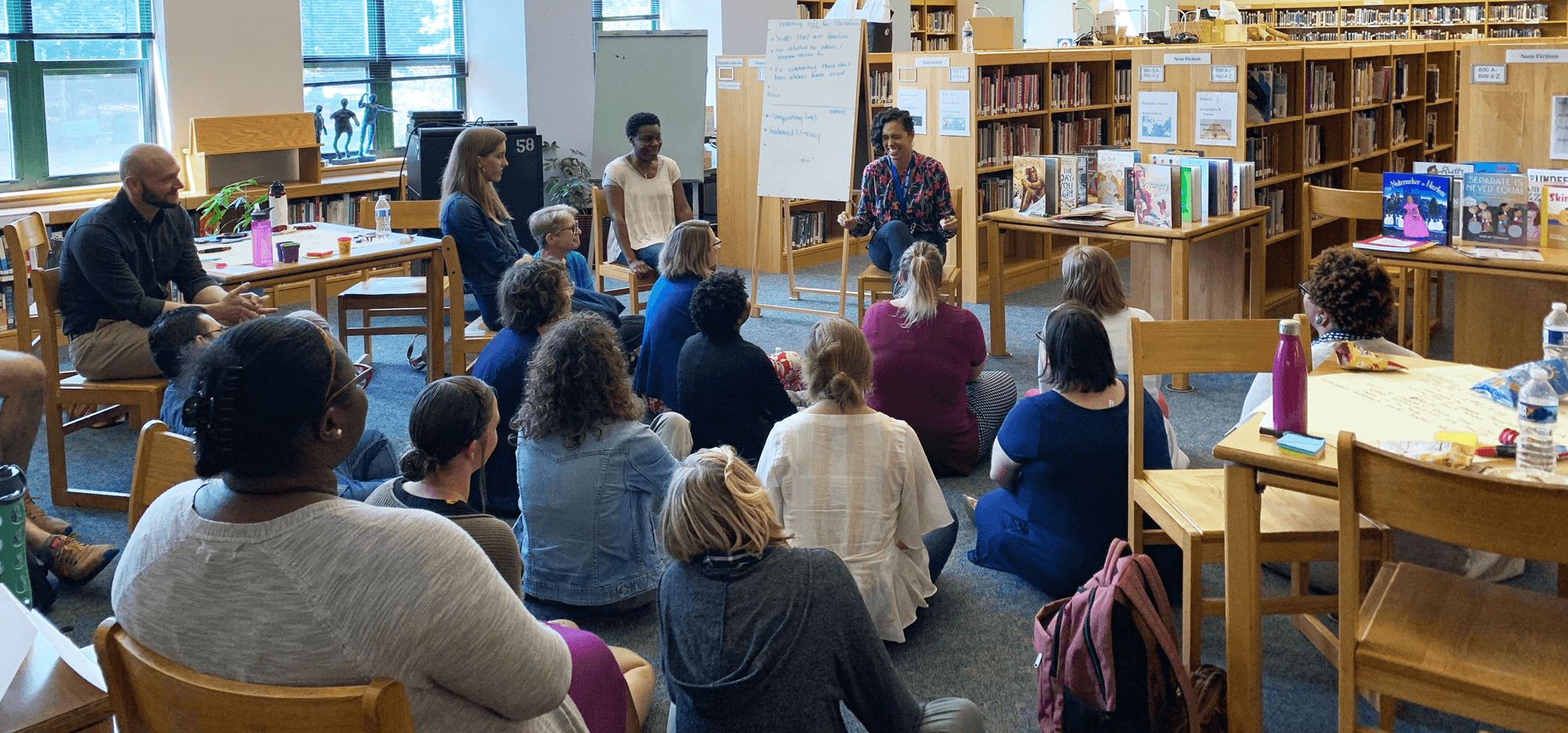

It’s a Saturday in mid-September, and groups of students and parents have arrived at Grey Culbreth Middle School in Chapel Hill to attend workshops and to learn about mentorship and the power of relationships. The district’s newly formed Office of Equity and Inclusion is hosting the event, with students of color, parents and community members now filling the space.

Among the day’s activities, students as young as elementary age participate in circles, sharing their personal experiences, their feelings about school and their insights about classroom and school culture.

In these circles, students feel safe to reveal their day-to-day experiences at school, including the ways that the school supports them and the ways that school culture causes them harm.

This is where the work of equity and inclusion begins. Listening to children speak in these brave spaces, members of the Equity and Inclusion staff hear stories that sound personally familiar—and in these stories, they see opportunities to build more equitable schools.

For Hispanic Heritage Month, TEACH North Carolina interviewed Dayson Pasion, Esther Mateo-Orr and Trilce Marquez, three equity specialists for Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools. We talked about the crucial work of their office and how their personal identities as Latinx educators shape their approach to the work.

In 2013, Chapel Hill – Carrboro City Schools created a vision statement around equity in schools, expressing commitment “to promoting the rights, welfare, and educational needs of all students through high quality, rigorous instruction in order to prepare future leaders for a rapidly changing world.”

The district further recognized that “This can only be accomplished in a school culture and climate that ensures that all students and staff are treated in an equitable manner with regard to the social and historical context of marginalized individuals.”

Read the full vision and value statements on the Office of Equity and Inclusion website.

With this vision in mind, the district formed the Office of Equity and Inclusion. Now with a team of equity specialists, the office is just beginning its work with students, parents and school administrators.

Each educator has an origin story—their reason for engaging in the work. For many, it stretches back to early memories of school and teachers who made an impact. Dayson, Trilce and Esther all had early education experiences that inform their approach to educational equity. They also experienced negotiating their identities as Latinx students and teachers inside the dominant culture of educational institutions.

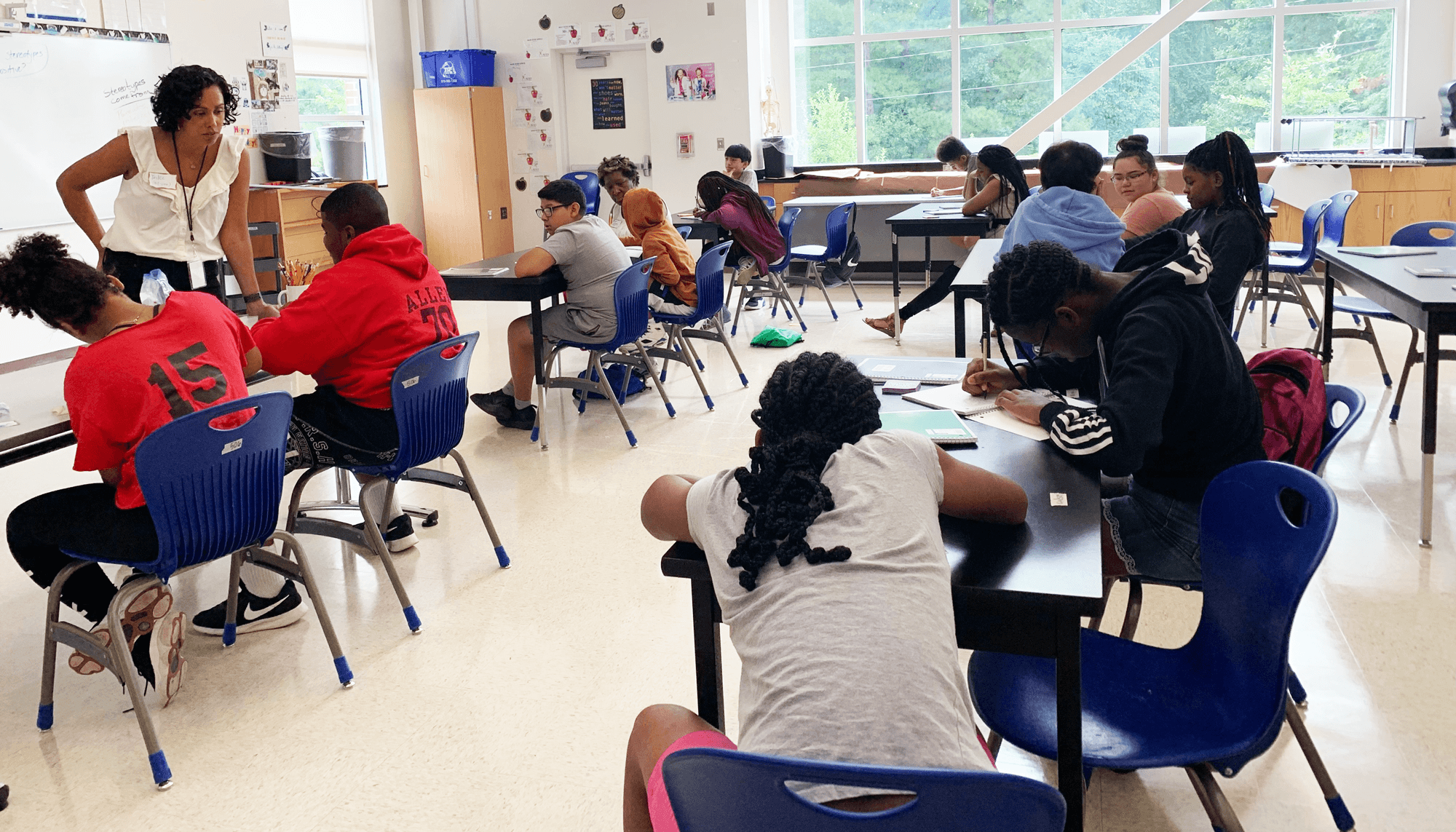

Before joining the office in June, Dayson Pasion worked in a neighboring district as a science teacher, STEAM coordinator and instructional coach. Growing up, he never really examined his own Latinx identity. He says, “as a student, the best way for me to survive was to assimilate to the dominant culture. I ran towards whiteness and all that that means.”

Dayson began thinking about his role and identity after becoming a teacher at a school where the majority of students were Latinx.

“One of the reasons I went into teaching, though didn’t realize it at the time, is that I didn’t have a teacher I could identify with. Recognizing that, I see these students having the same struggles I had. As a teacher, I realized I was perpetuating the system. I either had to accept that I was a cog in the wheel, or do something to change it. That’s why this work is important. I want to help create those spaces for students so that they don’t feel like they have to absorb the dominant culture.”

Though Trilce Marquez graduated from Chapel Hill High School, she lived in New York for the 12 years before coming back to the area. Similar to Dayson, she didn’t really explore her Latinx identity as a young person. In fact, she felt isolated by both the white culture and by people of color. As a light-skinned Latinx, she felt like she could never quite “pass”—not for white and not for a person of color.

She says, “I had maybe two teachers who spoke to me in a way that I felt like they saw me and understood me.” Yet those teachers, though few, made a deep impact as she began to think more deeply about her identity. “They helped me begin that process and look beyond the predominant white identity.”

“Later, as a teacher in New York, I began to really grow my own racial identity in different ways and began to explore what it meant to be a Latinx teacher and to help my students explore their identities. I found it to be the best part of my work, to give students a space where they felt like someone was seeing them. This made me want to help expand equity practices back in North Carolina.”

Growing up in a highly diverse small town, Esther Mateo-Orr experienced a tight-knit community with teachers who advocated for all students and provided challenging instruction.

“No one told me I couldn’t. There were kids who looked like me from many different ethnicities, and our teachers were highly motivated to help students succeed. When I left my little silo of a small mill town for college, that’s when I really faced barriers. I realized how poor I really was, and I first faced discrimination.”

Esther wanted all kids to have the supportive community she experienced growing up, so becoming a teacher was instrumental. She taught in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools for 16.5 years, then worked in Durham for several years as a parent advocate, coaching them and providing support in parent-teacher conferences. When her own daughters attended local schools, Esther knew there was work to be done with respect to equity. So, when Lee Williams started the Office of Equity and Inclusion, she was excited to join the team.

The work of creating inclusive spaces for learning encompasses every member of the school community. The district envisions school environments made safer for “those individuals who may be marginalized due to race, creed, color, national origin, gender, sexual/gender identity, class, socioeconomics, ethnicity, sexual orientation, cognitive/physical ability, diverse language fluency, religion, status as an English Language Learner, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or other characteristic protected by federal law.”

DP: As equity specialists, we’re here to support whoever we work with—building administrators, teachers and students. We work closely together to look at trends in a school to see what’s happening at that school in terms of equity and inclusion and to find ways to lessen and ultimately close the opportunity gaps in all our schools.

EMO: Recently, Trilce and I had the pleasure of sitting with elementary students of color. We sat in a circle to get feedback about how they are feeling at school. We asked questions like, “does your teacher talk about race in the classroom?” Students were so vulnerable in that circle and shared fascinating information that helps us do our work.

TM: Adults often have the idea that says we don’t want to put ideas in children’s heads about stereotypes, identity or racism, as though we might give children the ideas. But if you spend any time talking to students about their experience, even the youngest students can tell you about the trauma they have experienced in schools. And that’s important for adults to hear and understand, that students of color are experiencing trauma at schools, and they can identify it. They may be missing some of the language around it, but they know it.

DP: We’ve had similar circles with middle and high school students. So one of the questions we’re asking is, how do we recreate the space that we created at the power-of-relationships event for every school building? How do we create these brave spaces for students to have conversations and develop relationships? How do we build that capacity in the individual buildings?

TM: We are looking at these opportunities for students to share, because they help us grow and learn. As equity specialists, we can tell teachers about student experience and student trauma, but until it comes from the mouths of the students they see every day, it doesn’t seem as pressing. If a child can express their experience to a teacher, then teachers want to change and work harder to not inflict that harm.

Children are the biggest stakeholders. So, we gather these experiences from them and then we can ask the adults in the building to repair harm that’s happening and then find a way to prevent it.

EMO: As we have these conversations, we want to work with adults to repair harm first. That means understanding, acknowledging and accepting that harm has been done. Teachers want the best for students—no one gets into teaching who doesn’t want that. So, when you think you’ve done everything in your power for students, it’s really hard to hear you’ve done harm. We’re working to create a space where we can hear, believe and accept the truths students tell.

Then we can create a space that asks, how can I repair this with you? How can we think about ways to prevent that from happening again? And we’ve got to include students in that process.

DP: Right now, the district has four equity specialists and more than 12,000 students. So we will have to build capacity in individual schools, which means working with teachers and administrators.

TM: One thing that has stuck with me from the district’s Courageous Conversations training is an activity where we were asked to remember a sequence of words. Of course, everyone remembered the first word in the sequence. The idea is that we can all remember whatever we put first. What if we put equity first?

DP: One of the discussions we’re starting now is—how do we actively recruit and retain educators of color so that our teaching staff is more representative of our student body. What that looks like is still taking shape. For example, we are trying to create affinity spaces for educators of color to come talk about the ways we can support each other and acknowledge the trauma we may come into as adults.

TM: Be a teacher! 100% be a teacher! Young people give me such an immense amount of joy. As far as advice, future and current educators can create a teaching circle of influence by seeking people and spaces who help you grow, which includes calling you out! Those spaces include Twitter accounts, Instagram accounts, fellow teachers and mentors. I look for people who will challenge me.

EMO: For educators, when you receive your degree the learning really begins. You will learn so much that first year teaching about what you don’t know. Every year there’s just as much for me to learn as for my students. When we’re all learning, that allows for relationships to grow. You can learn just as much from your students as they can from you.

DP: Understand your “why”—your reason for teaching, and really evaluate it. Don’t go into teaching to “save” people. Don’t fall into the trap of teacher-as-superhero, because you’ll burn out quickly. Teachers are people and not superhuman. You can’t do everything.

Whether you’re a current teacher working through the process of repair and prevention, or a future teacher who is just learning about these issues, the team agrees: “give yourself grace.” In your work and your learning, give yourself the grace to grow.

And speaking of growing, the team offers this short list of resources to start building your sphere of influence and challenge. You can follow these organizations on social media, subscribe to newsletters, or get involved.

TEACH North Carolina can help you take the next step to a career in teaching, no matter where you’re starting.

Want the inside scoop on life as a teacher? Talk to a teacher and ask away!